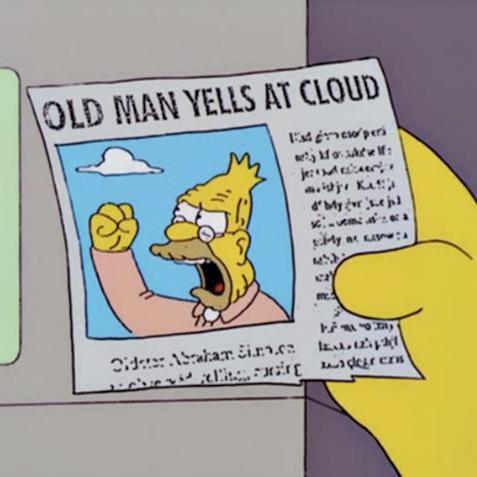

The ongoing fiasco of Twitter, once my favorite social media site, has put me in a nostalgic mood. The last decade or so of the internet’s development can be characterized as an ongoing and accelerating dismantling of open APIs and organic interactions in favor of walled gardens tended by algorithmic logic steering eyeballs and outrage in support of private profit. I’m an old man, so I feel I’m well in my rights to shake my fist at the clouds and insist that the young whippersnappers do not understand how much better the old ways were. We used to read our news feeds in a command line shell, dang it, and we LIKED it …

But actually, I rarely read my news feeds in a shell (though I could if I wanted to). By the time I started using Usenet with much regularity, I had “upgraded” to Windows 95 (I had a dual-boot system going with OS/2 Warp for a while – I supported OS/2 2.0 at work, and was pretty jazzed about an upgrade to OS/2 Warp (true 32-bit multitasking! Object REXX as the core scripting language! Every desktop object scriptable!) that lasted about 3 months before we wiped everyone’s workstations and installed the abomination that was Windows 95 … but I digress, as we old men tend to do). So I was using the newsreader client pushed by my ISP (Mindspring at the time, which was eventually acquired by EarthLink, an email address I still have because so much is still tied to it), though I dabbled a bit with other clients (mostly downloaded from Usenet itself as text-encoded binaries spanning multiple files that had to be painstakingly assembled and converted through a variety of utilities; which was the style at the time …)

Anyway … Usenet …

In the pre-Web, dial-up days of the mid-90’s, Usenet was where the action was. Or at least, it’s where I imagined the action to be. It was a network of “news groups”, arranged in a roughly hierarchical fashion, dedicated to a variety of topics. Whatever your niche interest, there was probably a Usenet group for it, where people around the world could ask and answer questions, proffer opinions, and sow chaos, as was their wont. Each news group had its own flavor and cultural norms, some being heavily moderated to keep the conversation germane and some being wild free-for-alls of the barest civility.

Prior to discovering Usenet, I had been on CompuServe, which had its own collection of bulletin boards, but those were open only to CompuServe members. Usenet was open to the world – if you could manage to get TCP/IP working (anyone remember downloading and installing Winsock? * shudder *), you could join the conversation; this was truly the cybernetic promise of all those William Gibson and Greg Bear books I devoured in high school and college, delivered in ASCII over a 2800 baud modem.

Because Usenet was an open platform, widely distributed and under no corporate governance, it was up to the user to curate their experience. There were actual physical books, available at your neighborhood Barnes & Noble, that could direct you to discover the best of Usenet, and there were some guides on Usenet itself, but trial and error seemed to be the best method for stumbling onto the useful and interesting news groups. I spent some time poking around in quite a few – there were news groups dedicated to all manner of computer technology, to literature and books, to languages and history – but the one that grabbed and held my attention most strongly was alt.folklore.urban.

In the Usenet taxonomy, “alt” indicates that the group belongs to a catch-all collection of topics with minimal moderation. It was where the porn went (“alt.sex.*”) and the software piracy (“alt.binaries.*”), but also pop culture (“alt.tv.*”, “alt.music.*”) and several “alt.folklore” groups (“.internet”, “.ghost-stories”, etc.). And the urban legend locus “alt.folklore.urban” was the most fascinating of them all.

Most of the alt.folklore.urban discussion threads followed a predictable pattern: the original poster would repeat a story they had heard from their neighbor’s mother’s cousin’s boyfriend’s barber about someone who woke up in a New Orleans hotel bathroom after a night of debauchery to find that their kidneys had been removed by nefarious black market organ dealers (and I swear this actually happened to my plumber’s brother’s wife’s dog sitter), followed by a series of responses repeating similar stories with subtle differences (it was Austin, not New Orleans; it was their spleen, not their kidneys), followed by a more scholarly (though usually of the independent gentleperson scholar type rather than a credentialed academic) parsing of the variations a la the Child Ballads. Often there would be a contribution from Snopes (later revealed to be David and/or Barbara Mikkelson, using a Faulkner-inspired moniker) that was especially witty at eviscerating the absurdities of the urban myth.

And I absolutely ate that shit up. I loved the wonderful weirdness of the urban legends themselves, which could range from the quaint and quotidian (like the Mrs. Field’s cookie recipe tale) to the unhinged and truly dangerous (racist tropes and conspiracy theories snuck in from time to time); but more, I loved the dissection of the legends, the tracing of their origins and variations, the subtle flaying of their crackpot logic with a deftly wielded Occam’s razor. I was in my first real job at the time – as an administrative assistant who carved out a niche in computer support – and I developed a little bit of a reputation as the know-it-all who would deflate whatever the tale-de-jour was in those pre-meme days. I had a couple of co-workers (or, as we cognoscenti would say, “cow-orkers”) who were especially vulnerable to a good urban legend, and I relished the opportunity to skewer them with the facts I gleaned from alt.folklore.urban.

Clearly, I was pretty insufferable in my 20s. I’m pretty insufferable in my 50s, too, but I’m better at hiding it. Working from home helps; it protects my cow-orkers from my sneering grimaces when they say something clearly in need of debunking; it’s why I never turn my camera on in Teams meetings.

The self-curation was definitely one of the things I loved about Usenet. I could compile my private list of news groups based on my personal interests, participate in the places where I felt I could contribute knowing that only like-minded people were listening, and lurk quietly in places where I wanted to build up some knowledge. There was no algorithm to say, “Oh, you like alt.folklore.urban, have you considered alt.commerce.urban-outfitters”? (I just made that last one up; alt.commerce.* would have been anathema to Usenet.) Instead, you found things by following cross-posted articles, scrolling through the menu of groups, or browsing those guides at Barnes & Noble.

But, if I’m being honest, the other big draw of Usenet was its exclusivity. Yes, it was open to the world, and the world definitely came calling. But it wasn’t “the world” in the mass sense that social media would acquire in the next ten or twenty years. There were technical gates through which you had to pass (I refer again to Winsock), as well as cultural and linguistic barriers: the alt.folklore.urban lingo of “cow-orkers” and “vectors” and “TWIAVBP” was opaque at first, but once you’d cracked the code(s) and could read the in-jokes and snide asides you felt like you too were one of the elect. I could try to explain it to someone on the outside of this little world, but I’m sure I would fail, and they would be left even more benighted than they started. And in alt.folklore.urban in particular, snark reigned – there was no greater faux pas than to be too earnest, unless you were being earnest about your snark. It was a comfortably toxic environment for certain kinds of personality disorders to which I definitely subscribe.

Usenet was my first real “social media” experience, which I define very broadly as interacting with strangers on-line within some (well- or poorly-) defined cyber space. While I certainly spent more time lurking than posting or responding, it was a good place to learn how to pick up social cues within the limits of a text-only medium, how to identify the unspoken rules of interaction, and how to distinguish useful information from the dreck. I think that my fiddling about with Twitter and Mastodon have largely been an attempt to recreate those heady days of discovery that I found on Usenet, when the internet was new and strange and completely un-monetizable. The past is indeed a foreign country, and all of our passports have been revoked.

The fate of Snopes feels like the perfect distillation of the fate of Usenet. I had largely moved from Usenet to web-based content by the early 2000s (oh the fickleness of technology!), and I was tickled to see around 2017 that they were one of the fact-checking services employed by Facebook and others to flag the flood of disinformation that had been swamping social media for a decade or more. It seemed at first that they were doing a valiant job, but something horrible had happened between 1995 and 2005: the internet had been taken over by the cow-orkers and vectors, ease of access had enabled ease of disseminating fabrications, and gullibility had taken the reigns and was driving us off a pretty impressive cliff. Also, there were a lot of personal and professional challenges at Snopes.com itself that undermined their mission.

In 1995, I was pretty sure that the rational dissection of falsehood was the surest path to progress and truth. In 2022, I’m not so sure. Debunking falsehoods seems only to entrench the falsehoods; logic is not a weapon that can defeat illogic, if the illogical is backed up by vim and vigor. The alt.folklore.urban ethic never had to grapple with the kinds of people Sartre identified in his remarks on arguing with anti-Semites:

They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti-Semites have the right to play.

It never had to face the widespread and totalizing madness of QAnon and related nonsense; and it had no weapons with which to fight the many heads and tentacles of the Algorithm and the logic of Engagement. For all its weirdness and snark, alt.folklore.urban and its Usenet kin belong to a simpler, gentler, and probably better age than the one we’ve built for ourselves since then.