The first thing you need to know about this story is that it’s true, more or less. When I was an undergrad at a small Catholic liberal arts school in the Upper Midwest in the 1980s, I was one of the editors of our quarterly literary journal. We published mostly heartfelt breakup poems and the occasional attempt at avante garde stories, as one would expect. But one issue we got an envelope of really raw, evocative, and somewhat disturbing poems submitted under what was clearly a pseudonym. I was about 80% sure then (and about 70% sure now) that I knew the poet responsible, but he denied responsibility. In any case, they were so much better than anything we had ever seen before that I demanded we take them; I recall the editorial board (three English majors, which meant four or five opinions), was split 2 to 1 in favor, and our advisor agreed we should take the risk — I repeat, “small Catholic liberal arts school,” and these poems were pretty sexy.

When the journal went to the college printing services, though, someone there took one look at these poems and refused to let them be included. I was, naturally, incensed — I was reading a lot of Joyce and Pound at the time, and so thought quite highly of myself — and there was a stand-off that delayed publication until after Christmas break. It apparently rose to upper echelons of the administration, and was a topic of conversation at the president’s holiday dinner — the rejected poems were floating around the administrative offices, and probably got more readers than if they had been printed with the rest of our lovesick drivel. In the end, the poems were pulled, replaced by a note about how incensed I was, and I got a story out of it, which I presented at my senior reading in the spring semester.

Anonymous poet, whoever and wherever you are, thank you for shaking things up!

Joseph K. ran a publishing company in the shadow of the Castle.

Perhaps “publishing company” is too grand a title. Joseph K. kept a battery of six or seven (depending on repairs) manual typewriters, a crate of carbon paper, and a large stapling machine in his basement. Every weekday a cellar door behind his house would open to the alley which connected with the city’s main avenue, and an intermittent stream of people would slip inside. Different people every day; Joseph K. seldom knew their names. Faceless, nameless, and unpaid, they would pound their fingers numb on the rusty typewriters, punching inerasable black marks onto the yellowing paper behind the carbon sheets. When the stack of manuscript sheets became a novel or a play or a book of verse, the large stapling machine drove a piece of wire into the top left corner. Then the stack of stapled pages would slip inside someone’s coat or purse and slip out into the streets to pass from hand to hand, read and praised and stained with coffee, all quite privately.

In his office upstairs, Joseph K. traced a blue pencil along handwritten or hastily typed novels and plays and books of verse. For six hours every day, including weekends, he marked corrections in the margins and stacked the pages in order and sent them, by way of an old dumbwaiter, to the basement. He rarely went down the two flights of stairs to the basement himself. He was ill, for one thing, and easily tired out. For another, Joseph K.’s profession as editor and publisher was unofficial and probably illegal.

At the Castle, which brooded above the city, Joseph K. was known as “MR15389, Convalescent, Classification B.” Which meant that a meager check came to him every month which afforded him groceries, a new coat every other winter, an occasional cigar, Sunday papers, and box upon box of blue pencils.

“That last novel by John M.,” said an author in Joseph K.’s study one day, “the one with the scene of pigeons in the park at dusk, was beautiful and moving.”

“Yes,” Joseph K. said with a sigh. He pushed his work into the corner of his desk and laid his pencil down. “It’s a shame no one reads our books.”

“Some do, though,” said David L., the author. “And that’s better than none.”

“But it should be more. Look at all the work we put into each book — each page.”

“Without a press, it can’t be done.”

Joseph K. sighed. Restrictions handed down from the Castle made owning a printing press difficult bordering on impossible. Forms signed by the proper ministers and stamps pressed by the proper directors could give one access to the State Surveyor of Communication Needs who would assess the expressed desire for a press and offer his recommendations to the board, who would review the surveyor’s findings, suggest further studies, and relay the board’s suggestions to the Senior Minister of Internal Affairs who, with the Emperor’s seal, would return a verdict to the patiently waiting publisher saying yea or nay. A similar process enveloped the ordering, the shipping, the licensing and the operating of the press, if permission first were granted.

“We should have our books reviewed, praised, sent far and wide across our country, and studied in schools and universities.” Joseph K. coughed fitfully into his tattered cotton handkerchief.

“Some go abroad,” David L. said. “They slip over the borders in suitcases and portfolios, and are translated and printed and sold in bookshops.”

“But in our own country,” sighed Joseph K., “in our own language.”

“There is nothing to be done,” said David L. upon taking his leave.

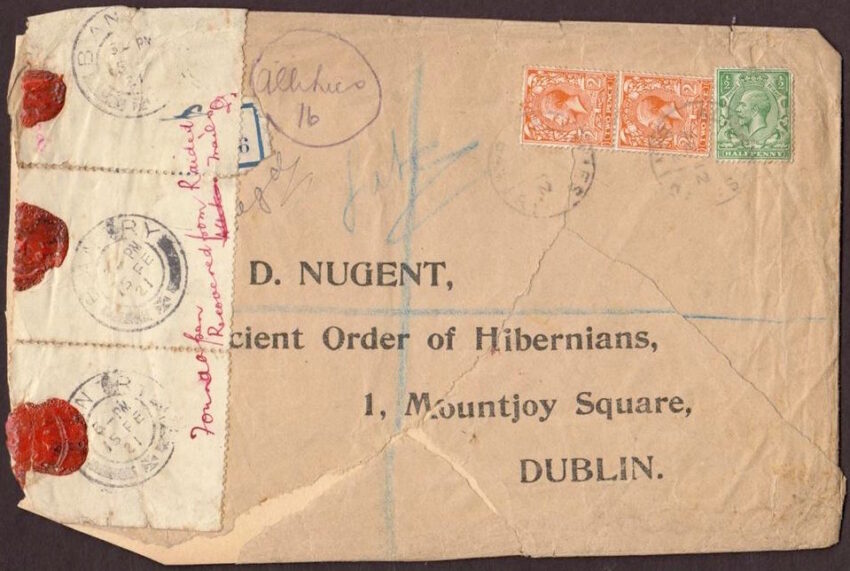

Joseph K. watched the author through his window, sneaking down the avenue and into the alley kitty-corner to the house, furtive glances darting over his shoulders. Then Joseph K. pulled a crisp brown envelope from his top drawer. For a long moment he held the envelope open, and then he thrust the hastily typed novel that he had been editing into the envelope and sealed it before he could doubt his decision. With a shaky hand he scrawled an address across the envelope’s face.

Mr. N. stacked the mail carefully in the grey trays on his desk: bound for the capital, bound for the provinces; to be sent to his direct superior, to be sent to his peers (for Mr. N.’s position granted him only equals, not underlings). Very rarely a piece came addressed to his position; these he placed in the red tray beneath his desk, to be read later and possibly mimeographed for his various files. Even more rarely a piece came with his own name on the label — these he slipped into his briefcase to be read on the long tram ride from the Castle to his home in the suburbs. One such came today; he held it carefully, reverently, in his hands, and then put it away for the evening ride. The crisp brown envelope fit in the upper pocket of his briefcase, one corner poking out above the tattered black silk.

Mr. N. thought about the envelope from morning until evening; he held it under his coat while waiting at the stop. As soon as he had found a seat in the back carriage, he tore open the gummed flap and pulled the contents into his lap. The thick pile of course paper felt heavy against his legs, and he suddenly felt ashamed to be in possession of it. On the hour-long ride out from the city, he read only the manuscript’s title.

Late that night, after his family had gone to bed, Mr. N. read the manuscript by the kitchen light. At first he was so gripped by shame and fear that his eyes skimmed across the pages, catching random words, making no connections between them. Eventually, though, his eyes and his heart slowed, and he read with care. It engrossed him: the plot, the characters, the language — drew him into its world and made him forget himself. Near dawn he began to read briskly again, trying to beat the sun to the last page. Though he had not slept at all, Mr. N. felt strangely refreshed.

Once in his office again, though, the shame and fear returned. What had he done? What had he read? Fearfully he tore off a sheet of memo paper from the pad on his desk and wrote a brief letter to his direct superior.

MEMO

To: Director of Correspondence, Section B

RE: Contraband manuscript

The enclosed manuscript, received yesterday, 5 October, requires supervision at a level higher than my own. With grateful sincerity,

Mr. N.

enc., cc.

When the memo had settled into the manila inter-office envelope and the inter-office mail had been taken away by one of Mr. N.’s peers, he felt very much more at ease. The rest of his mail was addressed to his position, not his person.

Ms. B., Director of Correspondence, Section B., was a very busy woman. She prided herself on her busy-ness; she said to every visiting underling, “Be brief — I am a very busy woman.”

She received the manuscript and memo with some displeasure. She sighed — a sharp, high sound from her diaphragm — and rolled her eyes to the overhead lights. Mr. N. had followed the chain of command, a virtuous act, and so could not be held at fault for the breach of protocol. At fault was the author of the manuscript, known to Ms. B. only by his/her initials, who should have sent the manuscript on the State Surveyor of Communication Needs. Without reading the stack of sloppy pages, Ms. B. slipped the manuscript into an envelope and addressed it to the proper office. As was proper to protocol, though, she copied the pages on the office mimeograph machine, filing it in the near-empty hanging folder marked, “Non-Standard Memos Sent On.”

The Emperor looked down benignly and wisely from the State Surveyor of Communication Needs’ wall. Mr. R., titleholder, was a great devotee of his nation’s federal system — a federal man through and through. Through him came all the requests for broadcast and print media from his state; through him went all the responses from the government. “His state” — he had even come to think of it thus, though of course he hailed from the capital, and had never visited the provinces.

Mr. R. read the memo first — a copy of the underling Mr. N.’s initial note, and then Ms. B.’s meticulously brief statement, then the first page of the manuscript. He was puzzled at that page. It was long, filling the paper to inch-wide margins on four sides, and written in a discursive, unhurried style. The author was not an accomplished memo writer.

His position was an important one, so Mr. R. had no time but for a perfunctory skimming of the first several pages and glance at the last, which was much like the first. Nowhere could he find a request for federal aid — certainly not Form 835QJ Yellow, the second sheet of six carbon pages necessary for proper federal attention. Such being the case, the manuscript seemed not to apply to him.

Mr. R. looked through the federal office directory for the appropriate recipient. This search required a discernment of the original sender’s intentions. If not a request, then what? He decided, finally, to send the manuscript to a lower echelon position of the office for Propaganda and Ideology, with a memo explaining his dilemma.

After filing a photocopy of the manuscript, Mr. R. sent the envelope onward.

Mr. G., Junior Minister for Propaganda and Ideology, was the fifth and last in his office to receive the manuscript. He was the coordinator of his office — the Senior Minister being situated in the cabinet offices — and prided himself in the informality and camaraderie of his management style. Much was to be gained from such a style, which made the workers feel at home in the office and gave them a personal stake in the task.

Much was to be lost too, though, such as efficiency. The chain of command was none too strictly applied, and some items of questionable meaning were often shuttled across and down before rising up to him. Such an item was the envelope that found its way to his desk after nearly a week in the office.

Mr. G. opened the envelope and looked with bemusement over the memos, attached with a pink paperclip to the front page of a lengthy manuscript. The first four were business-like and terse, signed by workers in other offices. The next four were chatty and informal, all from his own office. He was proud to see statements like, “None of us know what to do with it — can you think of something?” on office memos. It meant his leadership was working.

He set the stack of memos aside and began to read through the dog-eared, heavily-worn manuscript. Drawn into it at quarter to ten or so, Mr. G. was still reading when the workers in his office began to trickle out around four o’clock. Other papers piled up on the corner of his desk, but Mr. G. ignored them. This manuscript he found supremely interesting and enjoyable.

When he finished reading the sloppy pages at five fifteen or so, Mr. G. pulled out a pale purple sheet of stationary and began to write a careful though playful critique of the ideology implicit in the manuscript, refuting it point by point according the Emperor’s present concerns. This was a typical part of Mr. G.’s job — ideological review of unpublished documents — and he sincerely loved it. It was the highest form of intellectual gamesmanship to seek out and elucidate the ideological inconsistencies in the Emperor’s foes, and to find and often create ideological consistency in the Emperor’s statements. The present Emperor made the game particularly difficult and enjoyable.

After writing his critique and copying the manuscript for his files, the question still remained of what to do with the manuscript. The series of memos suggested that the intent of the original sender was uncertain. No one seemed to have any clue.

One with a more playful mind, like Mr. G., might have a better insight. Perhaps the sender merely meant to see how high in the Castle his pages could go? It was a commendable, if dangerous, game; Mr. G. could accept it and play it as well. He put the memos, critique, and manuscript back in the now-tattered envelope.

His superior, Senior Minister H., was notoriously dry and unamusable — certainly not a candidate for the manuscript. But Senior Minister S., Overseer of Transportation, was a funny and playful woman, the only cabinet officer Mr. G. ever associated with at cabinet parties. He sent the envelope to her.

The Emperor’s next cabinet party, held at the Winter Palace on the outskirts of the capital, was abuzz with the manuscript that had taken a strange, circuitous course through the Castle offices and was at last in the hands of the Emperor himself.

Quite a few Directors and Junior Ministers and Undersecretaries had read the manuscript in its entirety, sometimes having poured over their own copies several times, and carried on erudite and heated debates about its plot, its characters, and its language. The levels above and below these middle-managers were less well acquainted with the work, but had read enough to talk knowledgeably about the issues that it raised.

A small storm of memos had followed the manuscript through the office, as superiors demanded news of the envelope from underlings, as underlings explained key elements of the work to superiors, as peers argued the merits and disappointments of the words. An unconfirmed rumor had it that one Under-Secretary of Agriculture and Research (perhaps Ms. T.?) was tracing down these secondary memos to collect them together as a compendium to the original manuscript. This research had even created its own sub-storm of memos.

“It is quite a lively thing, quite a lively thing,” the Emperor, M. the Divine, said of the discussion of the manuscript. “It does perhaps bring life into the offices again. I must read it.”

“Has it reached Your offices yet, Your Eminence?” asked his aide, Msr. de D., a small, rodent-like man.

“It has, it has,” said the Emperor. “But I have not had the time, I have not had the time. It takes such time these days for reading…”. .

The Emperor’s voice trailed off as he turned away from Msr. de D. and walked into a cluster of arguing Junior Ministers.

Joseph K. had nearly forgotten that he had even sent the manuscript off to Mr. N., Clerk of Correspondence, when the long brown envelope, much tattered by its journey, arrived on his desk. A large white label had been pasted onto the front, bearing his address, but underneath he could see the ridges from other labels, the black and blue squiggles of other names and addresses, and he remembered that he had been the first to post this package.

He coughed and shook as he opened the envelope. The manuscript, tattered and smudged, spilled out onto his desk like a burst from a fountain. Another manuscript, printed on much cleaner paper in much cleaner type, spilled with it — it seemed to be a transcription of memos, with comments and footnotes stretched across the pages. Mimeographed memos held together by a pink paperclip fell out next, landing beside his box of pencils. Finally he found a letter, printed on Imperial stationary, pressed with the Imperial stamp, and sealed with the Imperial standard.

Joseph K. began to read the letter.

“Dear Joseph K., MR15389;

This letter concerns a manuscript received October 5 of this year in the Office of Correspondence, Section B. Its origin was traced to your home via agents of Internal Issues.

Said manuscript was received without appropriate forms or explanations; its intentions were never made properly clear. Hence, appropriate action could not be followed. We regret to return said manuscript, with comments by the various officials who dealt with this issue, without taking the action you might have desired.

In the future, please be sure to address requests and petitions to the proper offices. Refer to your copy of the Imperial Handbook for Citizens, available at your post office, for information. We are busy here, working for our citizens’ interests, and cannot, for efficiency’s sake, always make the time for unclear requests.

Your Servant,

M. the Divine, Emperor

enc.

cc.

tb:pl.”

Joseph K. read the letter several times, feeling a bit disappointed, and a bit elated, each time. He gathered the pages together again and slid them carefully into the bulging envelope.

In a firmer hand than the last time, Joseph K. wrote, “Ms. Q., Clerk of Correspondence, Section W,” across the front of the crisp, new manila envelope.