I’m an Americanist with an Irish soul — I swing between the Faulkner and Hemingway poles, though obviously I have a great affinity for Kerouac and the Beats (I did a big research project as an undergrad on Kerouac’s Quebecois roots), and Joyce is the bomb, of course.

The summer everyone read Faulkner, I read Hemingway. Out of spite.

While lugubrious sentences drifted through the nation’s consciousness like the broad muddy snake of the Mississippi, spinning off tributaries that ended in kudzu-choked swamps festering with secrets and lies, swirling with hidden maelstroms of meaning that turned the river of words back on itself, hiding treacherous sandbars that snared the unwary and foundered their boats so ill-fitted for navigating that mighty course, I read short sentences. Declarative sentences. Fragments.

It was, if you’ll recall, a sweltering gothic summer that promised to reveal mysteries and did just that: it revealed mysteries of many layers, water-logged, silt-choked mysteries that beckoned with their clues to be dug like aching graves, that begged to be courted and teased and fondled back behind the Jefferson drugstore but in the end gave up no answers, in the end met furious, rapacious attention with a blank idiot stare. It was a summer of bastard children and skeletons in the ice box, of rumored miscegenation and fecund madness, a summer of moist days, and nights that gave no relief despite their cool, gentle fingers kneading our temples. That summer it seemed every family was a fork of the Snopes line, that every mother was failed by her children’s poor burying skills, that every father’s son turned traitor to half-sibling secrets, that every sister crept from her window in the shadowy night to meet minstrel boys by the tarpaper shacks where blind sharecroppers played the blues on guitars strung with wires purloined from cotton bales.

I went fishing.

The glossies were full of sackcloth and gingham, last year’s belles drowning in shapeless shifts and their beaus decked out in homespun trousers that lumped suggestively when they squatted to check their trotlines for catfish. High lonesome gospel wrestled with tales of jilted lovers and honor duels on the radio, and television gave brooding stories of families clambering to reach bottom in a Gordian knot of tangled bloodlines that could end only in a blast of cleansing fire and redemptive murder. It was a stifling summer, a windless summer, a summer of sweat and blood and cool nights under the live oaks drinking whiskey and lolling in the sweet embrace of regret.

I wore flannel. I threw my fly rod in Lake Michigan. The clear water was cool on my ankles. At night I listened to jazz and remembered the Rive Gauche and the ware before that. But not so much the war.

That was the summer everyone had a drawl. Even at the tackle shop in Escanaba, where I stopped for bait and bourbon on my way to Lake Michigan, the clerk took his time to round his vowels and stretch his directions into a tragic story about Vern Sampson and the dark thing that happened to his son one cold winter morning when he went to milk the cows in the barn Vern’s great-grandfather built from the blood money of selling uneven shot to Union boys mowed down in Shiloh’s buzzing Hornet’s Nest on a long-ago April morning.

I handed him my money. I waited for my change. At the crossroads I turned left.

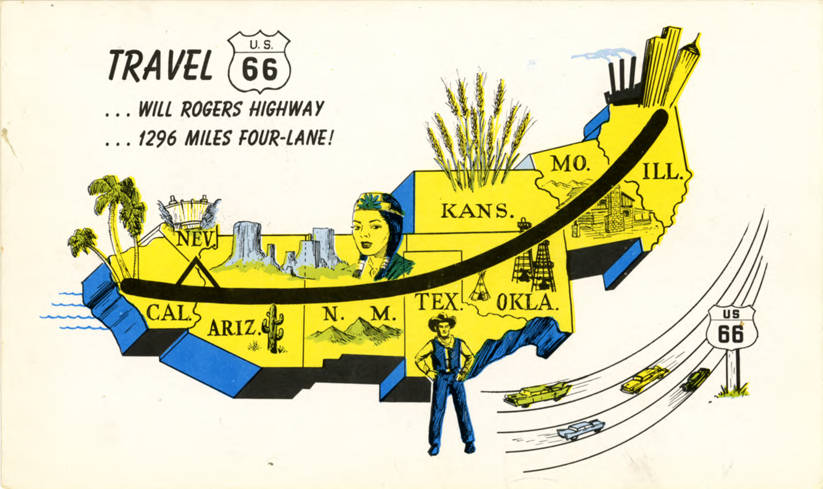

But just when it seemed the country had embraced its torpor, when the summer days had grown weary and stank so sweetly of lovers and causes lost to the slow drift of Old Man River’s lazy march past fields that Sherman burned on his long ecstatic tour of Dixie’s mossy manor houses, just when it seemed we had turned in upon ourselves to love ourselves as only kinfolk can, the Faulkner summer ended with a cold blast out of Lowell and a mournful soft trumpet blown on a corner somewhere in Chicago. Feet soothed in muddy sod itched for the road, ears grown accustomed to the jabbering voices of the past longed for something new cool fast hot big bold BLAST BANG and Route 66 opened wide was a V8 revving at the on-ramp across the wild country wide country alive with jive and popping with beatific beats and smoky bass and with Neal Cassidy riding shotgun the autumn nation threw itself onto the endless highway west, man, cool, man, west, man, west. The highways teemed with growling motors spinning on jet fuel dope distilled from hearts dripping with love and clogged the blacktop arteries with their fat desire. The finger-popping cool out of basement clubs multiplied into a sonic blast thunder that drowned out those old cotton gin chanteys in the autumn of our beatnik souls.

The kidneys I fried from breakfast that last day of summer smelled sweetly of the tang of urine. I would drive east on open roads past the stalled tangle of my countrymen, in search of more rivers where I could listen to the washerwomen gossip old as ancient nymphs and luxuriate in the eternal yes of autumn.