This story was picked up by Failbetter in 2004; they’re apparently still around, though they’ve gone through some iterations. It was inspired by an article about people superimposing maps of Dublin over their current locations so they could have odd Bloomsday journeys following Leopold Bloom’s steps. People are strange.

No one in Helsinki saw his weather reports. They didn’t need his two-minute segment, twice a day, nestled between the football scores and children’s cartoon based on the Finnish epic “Kalvala”; they could just look out their windows, stand on their stoops, and know to wear a coat today. The reports were for Finnish expatriates, nostalgic for Baltic winds and icy sidewalks, or for a handful of students learning the words “lumi” for “snow” and “pilvi” for “clouds.”

So Tomas didn’t have to be as accurate as he strove to be. They taped the two segments at noon and four, in the basement of University Productions in San Diego, and beamed them up to the satellite minutes later. But he was almost always late taking his seat because he had to check just one last time to make sure the high pressure bubble over the Baltic was still drifting toward the coast, or that the clouds over the Karelias were still kept at bay.

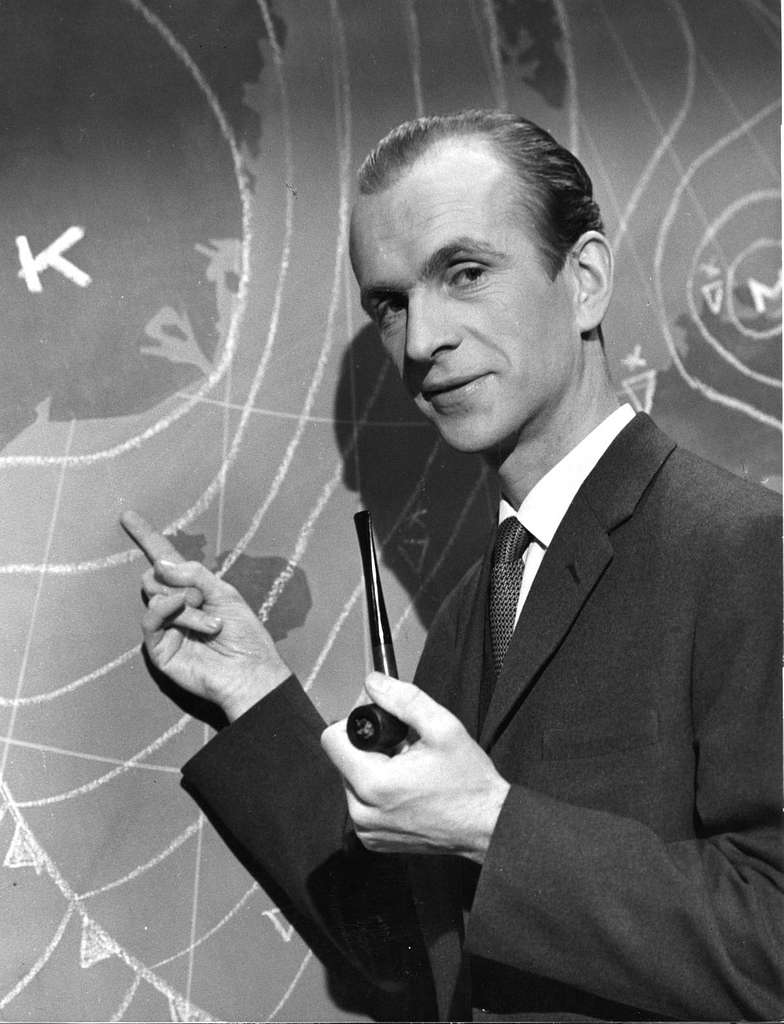

While he read the forecast into a microphone mounted on a battered steel desk, Jeannie stood in front of the blue screen with a white-tipped stick and pointed at the blank surface. She could see the map of Helsinki, overlaid with blue and red isobars, in the monitor over his shoulder, though to Tomas it looked like she was performing an intricate but meaningless dance. Jeannie had remained defiantly ignorant of Finnish, but somehow she always knew where to point.

Tomas knew that Jeannie was the other reason, besides nostalgia, that his audience tuned in. She came from Minnesota, a refugee from the same arctic weather he predicted for Helsinki, and was blessed with the blonde hair, fair skin, and playful and wholesome eyes of her Scandinavian ancestors. The San Diego climate had been kind to her, lightening her hair to the color of spun honey and darkening her skin to the tone of fresh buttermilk. In her cream-colored ski sweater, her hair tucked loosely into a silver clasp, she was both warmly approachable and utterly unattainable. Her smile, a testament to Midwestern orthodontia, shone through the blackest clouds Tomas could put over Helsinki.

University Productions rarely heard from its audience; the five foreign language channels they pushed into space were funded by subscriptions from schools and cable companies, so it didn’t really matter if there was an audience. But once or twice a week a letter would come addressed to “Finnish Weather Girl,” often as not in Finnish, not infrequently bearing a heartfelt marriage proposal. Tomas translated these for Jeannie, who sat on the couch in the employee lounge with her legs curled under her and smiled gently at the inevitable, “My family would be so proud to meet you.”

“That one was really sweet,” she’d say, or, “He sounds very nice.” Then she would direct Tomas to type a response declining the kind offer of matrimony, thanking her suitor for his flattering words, and wishing him the very best of luck.

“Why don’t you ever write these out yourself?” Tomas asked one afternoon. “I could give you the Finnish, you’d just have to copy it down in your own handwriting.”

She shook her head. “That would seem too—intimate. And I know I’d get something wrong, that they’d know I’m not Finnish. A typed letter seems more professional, doesn’t leave them with a little hope I might reconsider.”

Tomas nodded. He understood politeness. He kept a box of thank you cards in his desk, and mailed one out almost every week: to the mailman when he received an especially heavy package, to the manager of his grocery store if the apples were particularly ripe and sweet, to the road crew, in care of the Department of Transportation, who finished work on the highway exit to his home six days ahead of schedule. Sometimes he wept when he wrote them, overcome with gratitude at these undeserved kindnesses.

Tomas couldn’t imagine Jeannie as a child in a Minnesota winter, even though she had shown him a snapshot of herself in a pink snowsuit with a hood lined with synthetic white fur. Though she was only six years old in the photograph, he recognized her shining eyes, broad smile, and graceful stance, and he could see the Jeannie he knew growing inside the snowsuit.

“This is me,” she announced when she showed him the picture. They had been comparing childhoods the day before—his own, fifteen years before hers, he remembered as long dark winters lit by the streetlamps ringing the park where he skated, punctuated by brief hot summers when he dove into the pond at his grandmother’s farm to escape the clouds of biting gnats. Jeannie’s memories were not so different, though they also involved trips to the mall and Saturday morning cartoons.

“It is indeed,” he said and held her childhood picture up to the fluorescent lights. On the far left edge, almost falling off the photo, was an arm in a dark blue parka sleeve—her mother or father, perhaps?

“I used to love playing in the snow,” she said. “My mother would bundle me up and send me out for hours.”

“Don’t you miss it?”

“Not at all! It always got dark so early in the winter, and there was snow on the ground until April. Maybe a week of snow, but six months?”

“I miss it sometimes,” Tomas said. “It makes everything so smooth.”

“Until it gets gray and crusty. Or melts and you track mud around for weeks. Sunshine is just fine for me.”

“It’s a little too perpetual here,” he said. “It would be dull to forecast weather for San Diego.”

“But easy. You could record a year in advance and go on vacation. What are you giving Helsinki today?”

“The high pressure over Estonia will keep the clouds around for two or three more days. It will be foggy in the mornings.”

“Then I’m glad we’re in San Diego.”

“I suppose I am too.”

Though he wasn’t really sure how glad. When he looked out his window in the morning, he couldn’t tell the season. There were no trees bursting into brilliance in the fall, no smooth drifts of snow in the winter. Sometimes there was rain in the spring, but never enough to flood the streets. And the summers were too moderate and bright to make him long for January’s chilly winds.

He tried to make his own patterns to replace the rhythms that the seasons should have brought. For a month he would always wear something blue, and then abstain from blue for a month. He took cream in his coffee for a week, and drank it black the next. But his cycles were too short, abrupt, and arbitrary. He could never approximate the slow and gradual slipping of one season into the next, the surprise of waking up one morning in July to realize that somehow it had been summer for a week and he hadn’t noticed.

Helsinki’s weather gave him some sense of time’s movement, with storms marching in from the sea and sun pushing its way over the Karelidit mountains. Every morning he drew a pie chart of Helsinki’s daylight, with a tiny sliver of black in the summer and a tiny sliver of white in the winter. This chart reminded him that it was not eternally noontime everywhere.

He had moved to San Diego almost ten years ago to be with Susan. She was an American spending a semester abroad, he was a teaching assistant at the polytechnic, and they were crazy in love. Helsinki had not been her first choice—she had hoped for Sevilla or Pisa, but students who already spoke Spanish or Italian were preferred for those slots.

Susan would stay after his tutorials sometimes for help—she was taking the introduction to meteorology as an elective, and her math skills were not very strong. Soon they were meeting at the student union over bottles of Olvi Special to talk about the weather and places she had visited around Helsinki. And finally—on reflection, Tomas never could understand how it had first happened—she was spending the increasingly long nights in his one-room apartment as the winter semester neared its end.

They would lie tangled in the sheets of his hard student bed, the sputtery warmth of his faulty radiator augmented by the heat of their lovemaking, and Susan would tell him about the Pacific waves at Mission Beach and the stately flowering palm trees of Balboa Park. He closed his eyes and tried to imagine the crash of warm blue water, so different from the lapping of the Baltic’s cold, oily breakers. The burst of crocuses in the spring and blue harebells in the summer were a long-anticipated treat in Finland; his mother forced papery daffodil bulbs to bloom in her kitchen at Christmas, but the flowers always faded quickly in the harsh electric light. He had heard of palm trees clinging to the rocky cliffs of the Hebrides and Orkneys, carried there by strange Gulf Stream currents, but no such visitors ever crossed the North Sea to vacation in Helsinki.

After they made love, Susan always pulled on her sweater—a dark blue turtle neck, a pale pink cardigan—and lay across his chest in a shivering ball. Tomas missed the smooth sheen of her skin and sometimes told her so.

“Then come with me to San Diego,” she would say and nibble teasingly at his ear. “I can be naked there all the time.”

Sometimes they would make love again.

Jeannie kept a stack of sweaters in the closet next to their office. Her mother sent her a new one every Christmas, and again on her birthday in the spring. She only wore them during the weather reports, and then only when Tomas delivered chilly temperatures to Helsinki.

“I don’t know why she keeps sending them,” Jeannie said. Her birthday sweater was pale blue with a high neck. “I tell her not to, that I never wear them here.”

“Your fans like them.” The day before Tomas had translated a letter from a Finn in North Dakota who complimented Jeannie on the white cable knit sweater she donned for a late-season snowstorm.

“She thinks I’m going to move back. Wants me to have plenty of sweaters for the winter.”

“Will you?”

“Not until Minneapolis moves five hundred miles south. And maybe not even then. It snowed there on my birthday last year.”

“You could have worn your new sweater.”

“I can do that here. And then go to the beach after work. Is there snow in Helsinki today?”

“No, it should be gone now. There’s an unusual warm front coming in from the east today; the trees may bud early this year.”

Tomas had begun to miss the seasons a year after he moved to San Diego. The first year, he imagined the monotonous pleasantness to be like one of those winters when the Arctic Circle seems to creep almost to Riga—an aberration, a trick of the jet stream that happens only every five or ten years, sending icy winds screaming down Senate Square and drive even the hardiest Finns indoors. By the time Christmas came again with mild sunshine and carolers in polo shirts, Tomas was asking Susan if it would ever get chilly, even for a day.

“Why don’t we go to the mountains?” she said. “We can have a ski weekend.”

“Is there snow?” he asked.

“Of course. There’s always snow in the mountains. Just like there’s always sun in San Diego.”

And after only a few hours on winding roads crowded with cars loaded down with skis on their roofs, Tomas was standing with dry, powdery snow touching his knees. He laughed and made a snowball in his bare hands, but Susan didn’t smile when he cocked his arm as if to hurl it at her. So he let the snowball melt in his fist until it was a hard ball of ice and dropped it by his feet.

They spent their first morning in the mountains on the gentle beginner slopes because Susan had not been on skis since she was a little girl. But the lure of the lodge fire, hot chocolate, and spa sauna soon brought them back inside. After they made love in the soft downy bed, Susan returned to her habit of pulling on a sweater.

Tomas spent the next day outside while Susan sat by the fire, watching the skiers come and go. He borrowed snowshoes from the rental shop and explored the hidden crags and valleys above the slopes. Beside a trail far from the lodge he thought he saw bear tracks, but they might only have been badger or bobcat, made larger by the bright sun. If it was always winter here, he wondered, how would a bear know when it was time to wake up?

On the way back to San Diego, Tomas expounded on his theory that what time was in Finland, geography was in California. In Helsinki, one had only to sit still for the seasons to come; in California, one had to seek the seasons out, because they lived perpetually in one place. He wondered if foggy San Francisco was spring’s home. They never went back to the mountains.

When he got back to San Diego, Tomas sent a card to the rental shop to thank them for the snowshoes, and to warn them about the bear.

His cousin Viktor in Helsinki called sometimes to urge Tomas to come home and work for the shipping company. They always needed meteorologists, Viktor said, to predict delays on the North Sea routes. It was good work, good pay, and there wasn’t anything keeping him in San Diego since Susan left.

Though the work sounded interesting, Tomas always declined. At University Productions, the work was more varied. In addition to the weather reports, he wrote fifteen minutes a day of world and Finnish news, compiled the football scores, and made decisions about the programs to run in the six hours they broadcast. The “Kalvala” cartoon had been his idea, because he had honed his English on American cartoons. The vocabulary was simple but idiomatic, and the pictures reinforced concepts. He especially liked the Bugs Bunny opera cartoons, with Elmer Fudd as a Valkyrie chasing the rabbit through Valhalla.

It took Susan four years to realize, just weeks before their wedding, that she was more in love with the idea of him than the reality. By then Tomas was working at University Productions, filling the six hours of the new Finnish channel with old soap operas and dubbed American television shows. He stayed in San Diego; Susan, the last he heard, was living near Oakland with a real television weatherman.

“You’re just as real,” Jeannie told him. “Plus it must be harder to write forecasts for someplace thousands of miles away. When you write the local forecast, you can do just as well by standing outside.”

“No one uses our reports, though. Just to learn how to say ‘sataa’ or to hear a little Finnish to remember home. Or to watch a pretty girl in a sweater for a few minutes.”

“I don’t think anyone cares about the girl in a sweater,” Jeannie said.

“Except for your many suitors. And myself.”

“That’s sweet to say. But isn’t sweater season almost over?”

“I would still wear a sweater in the morning and at night. But the days are getting longer, it will be warm soon.”

“Then I’ll wear the brown one today; it’s not too heavy.”

The network manager told Tomas that the Finnish broadcasts would be suspended at the end of the month. It was early September, and Helsinki received fourteen hours of sunlight every day.

“There just isn’t enough interest,” the manager explained. He was a short, sweaty man who always wore a suit jacket, even in the summer.

“I understand,” Tomas said. “It’s not a popular language.”

“I hope we’ll be able to keep you and Jeannie on in some capacity. Maybe we can add weather reports to the other channels.”

“Maybe.”

Tomas imagined writing forecasts for Paris, Berlin, and Hong Kong, even though he had never visited those places. And how to handle the Spanish reports? A revolving cast of Madrid, Havana, and Mexico City? He could translate Jeannie’s marriage proposals in French and German, but he would be at a loss in Cantonese and Spanish.

“I can tell Jeannie the news,” the manager offered. “If you’re not comfortable doing it, I mean.”

“No, no, thank you, no. I can tell her.”

When Jeannie came in on the last day of September, the thermometer on Tomas’ desk recorded 56 degrees Fahrenheit, 13 Celsius. It was the lowest reading he could reach, with the air conditioner set to high and all but one of the fluorescent lights removed. She shivered and went out to the closet for a sweater.

“Is the air broken?” she asked when she came back in.

“Maybe,” said Tomas. He was wearing a sweater himself, a stained gray wool sweater he hadn’t worn since the ski trip with Susan six years ago. In all that time, he had never felt a temperature below a balmy 60 degrees.

“I hope I’ll need a sweater in Helsinki today.” She looked over his shoulder at the forecast on his desk. “Are those temperatures in Fahrenheit?”

“No, Celsius.”

“That seems awfully warm.”

“It is unusual.”

Tomas had found that he could rotate the isobars over San Diego and match them to Helsinki. He put Balboa Park over Linnanmäki Park, and the Gas Lamp District over Uspenski Cathedral. He imagined Finns in their shirt sleeves strolling Senate Square, deciding to stay away from work to enjoy the unusual warmth. Some, perhaps, would swim in the Baltic, though the sea would still be chilly. The San Diegans would grumble fiercely at the sudden cold, dig through their closets for sweaters that stank of camphor, but the chill would be replaced soon enough by their beloved sunshine.

Tomas sent a card to the pilot, in care of the airline, to thank him for the smooth flight and easy touchdown. His bags had not even shifted in the overhead compartment.

Minneapolis in October was milder than he expected. The sun set at six o’clock, but the air stayed warm until almost eight. Still, he could feel the cold moisture in the air that meant snow would come soon enough.

When he was settled into his new job writing weekend forecasts for television—a young woman, not unlike Jeannie, presented them in the morning and evening—he sent a letter to “Finnish Weather Girl,” in care of University Productions. The network manager had found work for her reviewing programs to include on the French and Spanish channels. He hoped that she would decline his proposal with a handwritten note.